The Difference between a Kitten and a Pig

By Kripamoya Das | Mar 02, 2012

Thirty-eight years ago I became a vegetarian. In all this time I have not eaten any dead animals, and I’ve avoided any food ingredients derived from animal body parts. No cows, sheep, pigs; no fish, no chicken – and, specially here in London, no jellied eels. Are you impressed?

No, I didn’t think so. Neither am I really. In fact, I hardly think of myself as a ‘vegetarian’ at all. Its been such a long time – all my adult life – that I’ve even forgotten the taste of meat. I just can’t remember it. And I never struggle with the temptation to eat meat. The thought just doesn’t arise.

I’ve arranged my life so that its easy for me to cook and eat only with vegetables and grains as raw ingredients. And I don’t have any friends who chomp on dead flesh, either. If I get invited to dine with other families, which I do often, then they are vegetarians, too. And the vegetarian food I eat is delicious, which makes it even easier to be a veggie.

But I still have to be careful. I’ve been so long living in this pleasant veggie bubble that the psychological processes by which I choose to not eat meat have been somewhat dulled. I don’t actively think about being a vegetarian very much. Like a muscle that’s wasted away, the part of my brain that discriminates between meat and non-meat has partially atrophied due to lack of exercise.

I’ll give you an example of my wimpy veggie brain-muscle: Some years ago I was on a train on my way up to Manchester. I hadn’t had any breakfast and I was hungry. Then a fellow passenger walked by with something mysterious in a brown paper bag from the buffet car. The smell wafted across my nostrils and immediately I became interested. It took me a full three seconds of rummaging through long-lost olfactory memories to classify the smell as ‘bacon sandwich.’ At which point my discrimination kicked in and I made a choice: “Oh, I don’t eat those…”

Which is not good enough, is it? As sleepy as I was that morning, I should have been alert and discriminating. Discrimination is good, you see. Discrimination, for so long abused as a bad thing, is actually a good thing. We all have to discriminate between things we can eat and things we can’t. Only babies and mad people don’t discriminate about what they put in their mouth.

Because if you eat things you shouldn’t you might end up with food poisoning, disease, death, monstrous karmic reactions – or all of the above.

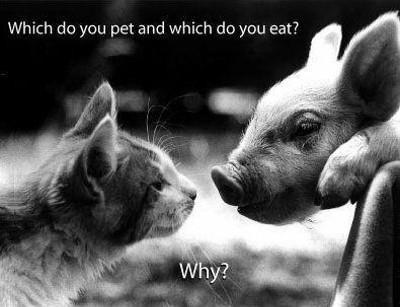

And this is something that has always puzzled me: why do we discriminate unfavourably between kittens and pigs? Why do we term one ‘pet’ and the other ‘food?’ Why do we want to stroke one and make cute baby sounds, then pick up the other, slice its rear end and stick it between two slices of bread? I’ve never quite understood that.

And neither has Melanie Joy, who makes quite a good case for preserving and refining our sense of viveka, or discrimination, in the video at the end of this short piece.

So a word to all my friends, specially those who have been vegetarian for a long time: Statistics from the Vegetarian Society reveal that the main reason given for their members abandoning a veggie diet is the bacon sandwich. Yes, that’s right. Do not underestimate that most humble of non-veg dishes.

And to all my Indian friends: I must remind you that bacon is part of a pig, which is an animal, and if you eat one – or sell one – you are betraying all that your grandmother held sacred. Doesn’t matter that all your English friends think you’re foolish for being a vegetarian for ‘religious reasons,’ or that you don’t want to be different from everybody else. Eating animals is entirely unnecessary, bad for the planet, bad for your heart and colon, and morally indefensible.